Over a year ago, at the SBL convention in Atlanta, I attended a session on reception-history in the Old Testament. One of the speakers made some preliminary comments that struck me. First, when asked why he didn't study history ("what was originally meant") instead of reception-history ("what was later made of the bible"), he replied that he simply didn't have the imagination it took to be a historical critic. But second, and in support of his cheeky comment, is that historical critics -- whether of the historical Israel, or the historical Jesus, etc. -- tend to operate under an implicit assumption: that

what is earliest is, somehow, best. And this is silly. The apocalyptic worldview of Jesus and his disciples wasn't necessarily better than, say, the gnostic one of the second century. Not least since Jesus was wrong about the world's imminent destruction... but aside from even the question of mistaken beliefs, visions cry out for reinterpreation lest they stagnate.

So too in the field of Tolkien scholarship. Interpretations of

The Lord of the Rings found in film, art, and role-playing games are often blasted for no other reason because they contradict what the author intended. I've been strongly reminded of this lately in the debate as to whether or not Balrogs have wings and/or can fly.

Let me be clear.

It is about 99.98% certain that Tolkien's Balrogs were wingless and could not fly, despite continued protests to the contrary. I won't go through every piece of evidence, just the highlights:

(1) When Gandalf confronts the Balrog of Moria, the text speaks of demon's "shadow reaching out like two vast wings". That's obviously a simile, not a description of literal wings. The text goes on to say that this shadowy form of the Balrog "stepped forward slowly onto the bridge, and suddenly it drew itself up to a great height, and its wings were spread from wall to wall". The wings here must be metaphorical, poining back to the simile just made. This conclusion can be rather easily drawn from other passages in Tolkien. To wit:

(2) If Balrogs could fly, Melkor would not have needed to try obtaining the secret of flight from the Eagles (see HoME II: The Book of Lost Tales II, The Fall of Gondolin). He would have already had it.

(3) Tolkien wrote of "the Eagles dwelling out of reach of Orc and Balrog" (see HoME IV: The Shaping of Middle-earth, Silmarillion). If the Eagles are inaccessible to Balrogs as much as to orcs, that pretty much puts to bed the idea that Balrogs can fly.

(4) Melkor eventually created breeds of dragons that could fly, and their description bears on the question at hand: "Out of the pits of Angband there issued the winged dragons, that had not before been seen; for until that day no creatures of his cruel thought had yet assailed the air." This obviously means that Balrogs, who existed prior to this time, could not fly. And certainly Tolkien never mentioned later breeds of Balrogs that could.

(5) The following text is often brandished by the opposing side: "The dwarves roused from sleep a thing of terror that, flying from Thangorodrim, had lain hidden at the foundations of the earth since the coming of the Host of the West: a Balrog of Morgoth." But "flying" in this context is an archaic term for "running from" or "escaping". We know that Tolkien often preferred the archaic, for instance when Gandalf cries out to the fellowship, "Fly, you fools!" -- not, obviously, telling them to grow wings and fly, but to haul ass before the Balrog kills them all.

(6) The following passage has wreaked havoc: "Far beneath the halls of Angband, in vaults to which the Valar in the haste of their assault had not descended, the Balrogs lurked still, awaiting ever the return of their lord. Swiftly they arose, and they passed with winged speed over Hithlum, and they came to Lammoth as tempest of fire." (HoME X: Morgoth's Ring, The Later Quenta Silmarillion, (II) The Second Phase, Of the Thieves' Quarrel). "Swiftly they arose" refers not to flying, but to the Balrogs' ascending or climbing out of caverns far below; and "winged speed" is yet another metaphor.

All of this evidence taken together proves, to me, beyond sane doubt that Tolkien's Balrogs were wingless and could not fly. Now, it may very well be that Balrogs could fly in their non-incarnate forms like any other

ealar in Middle-Earth, as argued, for instance, by Thomas Gießl (see

Other Minds Magazine, #10, Aug 2010, pp 4-12). But that point is so esoteric as to be trivial. Interestingly, Gießl thinks the Balrogs described in point (6) were indeed flying in their incorporeal state: "They flew to Lammoth because there is no reason to assume that they had taken on a corporeal form...since Manwe himself had slain them before" (Ibid, p 11). I somehow doubt even this, but at least Gießl gets the basics right. Substantively speaking, Balrogs didn't fly, and certainly the Balrog of Moria showed no capabilties on this point.

Having settled this matter (though I'm under no delusion the question has been settled in the minds of the opposing camp), let's take it to the next level. Is there anything

wrong with giving Balrogs wings, as so many filmmakers, artists, and role-playing gamers have done? Absolutely not. Readers of this blog know that I believe the worst adaptations are those which slavishly follow their source material and hang on the text's every word. This level of faithfulness, ironically, avoids interpretation itself, and usually kills artistic spirit in advance. Going back to the analogy of biblical studies -- "earliest isn't necessarily best"; what Jesus did, the gospel writers saw fit to change; and what the gospel writers decreed, later chruch thinkers upended in turn. This is a natural healthy process.

But we need to acknowledge what we're doing. If we like interpretations of Balrogs with wings -- as I certainly do -- we should be comfortable acknowledging our departure from the canon, rather than twisting Tolkien's original meaning to suit our tastes.

I leave you with some artistic interpretations of the Balrog. Click on the images to enlarge, and pay your money and take your choice.

This is my favorite Balrog portrayal of all time, by Flavio Hoffe. But it's obviously not true to Tolkien.

I really like this one too, by John Howe. It's a mighty aggressive wingspan.

This is another one by John Howe, his second swing at the Balrog when working on the films for Peter Jackson. And of course, this is the image burned in the minds of millions of people for over a decade now. That's not a bad thing, even if it has little to do how Tolkien envisioned his creature.

Here's Ted Nasmith, another renowned Tolkien illustrator, and one of the very few to eschew wings. Now, obviously this portrait is

faithful to Tolkien unlike the above three. But that doesn't make it the

better interpretation. I don't know about you, but I think this one not terribly impressive. (Ted Nasmith is superb with Middle-Earth's landscapes, but not always so with its peoples and creatures.) Put it another way: Ted Nasmith is a great "historical critic" but perhaps not the most outstanding "receptionist".

Here's Stephen Hickman's vision, which leaves the matter ambiguous, doing justice to all the shadows Tolkien harped on, but not boasting the best aesthetic.

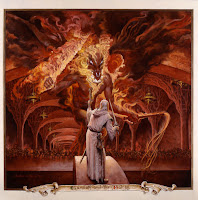

This one's curious. It's the cover of a role-playing supplement put out by Iron Crown Enterprises, which clearly avoids wings. Yet ICE assigned the Balrog dreadful flying abilities (as I mentioned in yesterday's

retrospective on Moria). Even in the text of the module there is no mention of wings. So here's an interpretation that allows Balrogs, apparently, a magical power of flight (even in their corporeal forms) but not wings.

But the elves of Amon Lind steal the show. They are a complete invention on ICE's part, a small group of Noldor who left Eregion in the Second Age to continue their controversial projects without interference or censure. Their hanging fortress in the Misty Mountains is a wonder, with transparent floors overlooking air, and walls containing pipes that play songs inducing a variety of spell effects -- sleep, fear, holding, calm, or stun. Their creations are staggering, and remind of alien technology, especially Sulkano's air boats made with the rare metal Mithrarian which negates the effect of gravity. There are also Elenril's breeding experiments, resulting in what he calls the "weapons" of Amon Lind, human and elvish subjects merged with mammals like snow leopards and lynxes. While these elves aren't really evil, they are certainly laws unto themselves, and their obsessions off-kilter, and there is rarely any disciplinary action taken on grounds of individual freedom.

But the elves of Amon Lind steal the show. They are a complete invention on ICE's part, a small group of Noldor who left Eregion in the Second Age to continue their controversial projects without interference or censure. Their hanging fortress in the Misty Mountains is a wonder, with transparent floors overlooking air, and walls containing pipes that play songs inducing a variety of spell effects -- sleep, fear, holding, calm, or stun. Their creations are staggering, and remind of alien technology, especially Sulkano's air boats made with the rare metal Mithrarian which negates the effect of gravity. There are also Elenril's breeding experiments, resulting in what he calls the "weapons" of Amon Lind, human and elvish subjects merged with mammals like snow leopards and lynxes. While these elves aren't really evil, they are certainly laws unto themselves, and their obsessions off-kilter, and there is rarely any disciplinary action taken on grounds of individual freedom.